In a previous blog post, we pinned down a definition for mode-covering vs. mode-seeking behavior for distributional divergences. When fitting $q$ to a target $p$, we studied the gradient norm of the divergence wrt $q(x)$.

| Divergence | Formula | $\partial/\partial q(x)$ |

|---|---|---|

| Forward KL | $\int p \log(p/q)$ | $O(p/q)$ |

| Bhattacharyya coefficient | $\int \sqrt{pq}$ | $O(\sqrt{p/q})$ |

| Reverse KL | $\int q \log(q/p)$ | $O(\log(p/q))$ |

By “plugging in” $q \to 0$ where $p > 0$ to the gradient, we can see how sensitive each divergence’s score is to undercovering regions with positive $p$-mass. By this sensitivity analysis, forward KL has strong mode-covering pressure, as $O(p/q)$ explodes when $q \to 0$. Bhattacharyya has less pressure, and reverse KL has even less pressure.

In this note, we’ll explore a different approach for quantifying mode-seeking vs. mode-covering preferences. We’ll study divergences in an idealized setting that enables tractable mathematical analysis, and produces a number that quantifies how mode-seeking vs. mode-covering each divergence is. This quantitative analysis will show that the Bhattacharyya coefficient is actually rather mode-seeking.

Setup

We consider a target $p$ with $m$ “heavy” modes with equal weight of $a$, and a light mode of weight $\psi a$ with $\psi < 1$.

We will consider two options for $q$:

- Heavy only (mode-seeking): $q$ that fits the $m$ heavy modes perfectly with mass $1/m$, and ignores the light mode

- Heavy and light (mode-covering): $q$ that fits both heavy and light modes by assigning $1/(m+1)$ mass to all modes.

Within each mode, we consider $q$ to match the shape of $p$ exactly. We further assume that the modes are very well-separated. This means even if $x$ is continuous, we can effectively model the modes as discrete bins from the perspective of $q$ and $p$.

For a given divergence, we will study the threshold $\psi$ where the divergence flips from favoring the mode-seeking candidate to the mode-covering candidate. As $m \to \infty$, the thresholds are:

- Reverse KL has threshold $\psi \approx 1/e \approx 0.37$

- Bhattacharyya coefficient has threshold $0.25$

- Forward KL has threshold $0$

For the reverse KL, when the light mode has relative weight less than 0.37 compared to the heavy modes, the reverse KL prefers to not cover the light mode. Thus, it is more mode-seeking. Meanwhile, the forward KL will prefer to cover the light mode no matter what its weight is, so it is strongly mode-covering.

Interestingly, the Bhattacharyya coefficient has threshold 0.25, which is similar to the reverse KL, making it fairly mode-seeking in practice.

Analysis

We’ll perform one analysis encompassing the reverse KL, BC, and forward KL, by using the Amari divergence family:

$$ D_\alpha(p||q) = \frac{4}{1-\alpha^2} \left( 1 - \int p^{\frac{1+\alpha}{2}} q^{\frac{1-\alpha}{2}} dx \right), \quad \alpha \in (-1, 1) $$

- $\alpha \to -1$: Reverse KL

- $\alpha = 0$: Bhattacharyya coefficient

- $\alpha \to +1$: Forward KL

When comparing the two candidate $q$s for a given $\alpha$, we can drop the coefficients and just focus on the power affinity, which we’ll re-express using $\beta = \frac{1+\alpha}{2}$:

$$ A_\beta(p, q) = \int p^\beta q^{1-\beta} $$

Now, let’s compute the power affinity for the two candidates, which we’ll call $m$ and $m+1$. Recall that $p$ assigns weight $a$ to each heavy mode, and $\psi a$ to the light mode.

The candidate $m$ assigns weight $1/m$ to each heavy mode:

$$ A_\beta(m) = \sum_{j=1}^m a^\beta (1/m)^{1-\beta} = a^\beta m^{\beta}. $$

The candidate $m+1$ assigns weight $1/(m+1)$ to all modes:

$$ A_\beta(m+1) = (ma^\beta + (\psi a)^\beta)(1/(m+1))^{1-\beta} = a^\beta (m + \psi^\beta) (m+1)^{-(1-\beta)} $$

Covering the light mode helps when:

$$ A_\beta(m+1) > A_\beta(m) $$

After some algebra, we get:

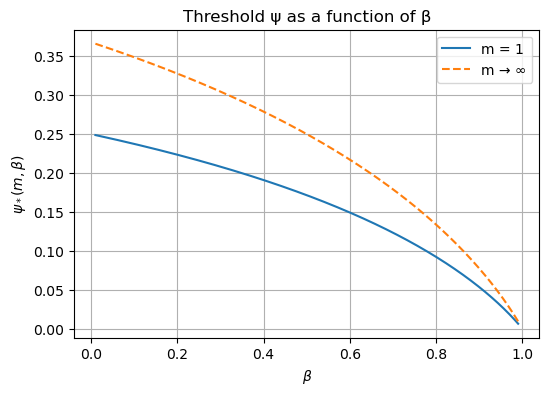

$$ \psi^*(m, \beta) = \left( m \big(1 + \frac{1}{m} \big)^{1-\beta} -m \right)^{1/\beta} $$

As $m \to \infty$, this is:

$$ \psi^*(m, \beta) \underset{m \to \infty}{\rightarrow} (1-\beta)^{1-\beta}. $$

As $m \to \infty$, the thresholds are:

- Reverse KL has threshold $\psi \approx 1/e \approx 0.37$

- Bhattacharyya coefficient has threshold $0.25$

- Forward KL has threshold $0$

Visualizations

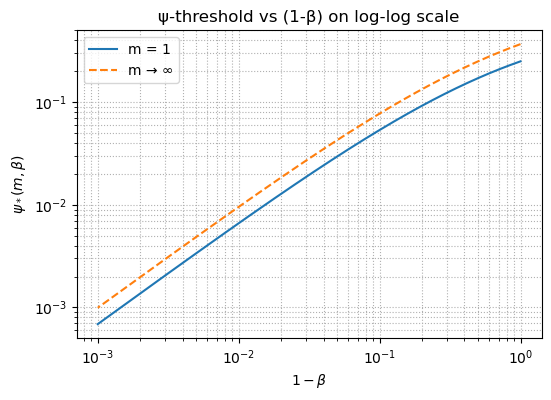

On the $\beta$ scale, the reverse KL sits at $\beta=0$, the Bhattacharyya coefficient at $\beta=0.5$, and the forward KL at $\beta=1$.

When $m=1$ (there is only one heavy mode), the divergences are more willing to pick up the light mode, even if the light mode weight is smaller. As $m \to \infty$, the divergences become less willing to pick up the light-weight light modes.

If we wish to obtain a divergence that is mode-covering sensitive to light-weight modes, of say 0.1 percent weight as the heavy modes, we will need to choose $\beta$ of 0.999.

Conclusion

This $\psi$–trade-off lens turns the vague idea of “mode-covering vs. mode-seeking” into a concrete, operational threshold: how light can a new mode be before a divergence stops rewarding you for covering it under a simple, uniform-over-kept-modes constraint. In this setting:

- Reverse KL behaves strongly mode-seeking, with a large, $m$-independent threshold $(\approx e^{-1} \approx 0.37)$

- Bhattacharyya/Hellinger is also mode-seeking in practice: its threshold tends to 0.25 as $m \to \infty$, meaning it will still ignore a mode only 4× lighter than the others.

- Forward KL is the only one that is unconditionally mode-covering (threshold 0): it always prefers adding any nonzero-mass mode.